Through a Glass Oldly: "St. Elmo's Fire"

My generation, Generation X, takes a willfully ignorant, hypocritical pleasure in bashing younger generations for their self-absorption and frivolousness. Why, when we were their age, we were rocking the vote! We were Desert Storming! We were watching our friends do spoken word poetry! We knew what it meant to suffer and sacrifice, all without sharing it on social media. The warm, soothing pool of denial has plenty of room, dive on in, fellow olds. Just don’t pay attention to the media that was made especially for us when we were young.

St. Elmo’s Fire isn’t a John Hughes movie, it just looks like one. All the indicators are there—attractive, upper class young white people, a fear of growing up, problems that aren’t really problems, non-whites being treated like leprechauns, in that no one can say for sure that they don’t exist, but no one’s ever seen one either. Actually, that isn’t fair to St. Elmo’s Fire. It does have one black character. She’s a prostitute, who gets less than two minutes on screen. Other than that, however, the so-white-they’re-clear main characters live in a fairytale Washington, D.C. populated only by other people who look exactly like them, where the most vexing problem is that they suddenly don’t have as much time to waste drinking and flirting with each other as they used to.

Boasting not one, but two insipid theme songs, it’s an ensemble comedy-drama, and like a lot of movies with too many characters, the writers are so busy herding them from one plot point to the next that they forget to make them likable or engaging. There are a whopping seven protagonists in St. Elmo’s Fire, all of them thinly drawn, none of then with a single redeeming quality, except that they’re good looking and dress nice. It’s a hard sell that the audience is supposed to relate to these characters, let alone care about what happens to them. Even the characters themselves behave more like cordial co-workers, as opposed to close friends drawn together by a love for wool overcoats and extraordinarily pale skin.

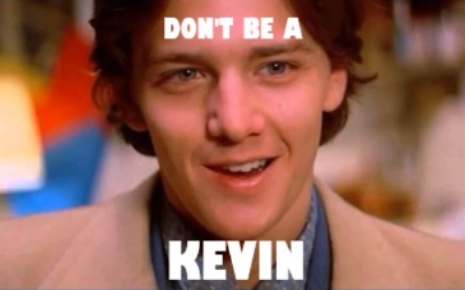

All recent graduates of Georgetown, the group of friends is led by Alec (Judd Nelson), a former campus activist turned aspiring yuppie Republican, and chronically unfaithful to his girlfriend, Leslie (Ally Sheedy). Kirby (Emilio Estevez) is obsessed with a former classmate, and that’s really all we ever find out about him. Kevin (Andrew McCarthy), the world-weary cynic of the group, is a writer—we know this because he smokes a lot, looks miserable, and says stuff like “Used to be sex was the only free thing, no longer. Alimony, palimony, it’s all financial. Love is an illusion.” Jules (Demi Moore) is the party girl, sleeping with her boss and supporting a coke habit.

Then, there’s Billy (Rob Lowe), a former frat boy turned wayward husband and father who would rather spend his free time wheezing into a saxophone and chasing women than see to his responsibilities. Billy is that most tiresome of archetypes, the lovable asshole, who gets away with things most people would find unendurable because he’s supposedly “charming.” This includes drunk driving, when he totals the car belonging to Wendy (Mare Winningham), the seventh and final member of the group, a virginal, wealthy daddy’s girl who is desperately, inexplicably in love with Billy. Everyone, including Wendy, who was injured in it, treats the accident as just Billy being incorrigible Billy, and shrugs it off. Wendy’s family is rich, they can just buy her a new car, so it’s treated as a minor inconvenience.

Why worry about such trivialities as drunk driving when you’re busy farting around trying to figure out which one of you is meant to be together? The primary plot arc is Alec and Leslie—Alec can’t keep it in his pants to save his life, but thinks that marrying Leslie will put an end to his incessant cheating. The long-suffering Leslie eventually ends their relationship, and within hours, Kevin, who has loved Leslie afar for years, moves right in on her. They sleep together, but when Leslie tells Kevin that she’s not ready to get into a new relationship a mere day after ending her last one, his reaction is one of “wha-wha-whaaaaaat?” shock and hurt. He put his whole life on hold for her without being asked, and this is how she thanks him?

Meanwhile, in the even less interesting B plot, Wendy pines for Billy, even after its apparent that he’s been inside more women than a gynecologist, including, at some point, Jules. Billy is the kind of guy who will try to talk someone into giving him a blowjob while parked outside his house, where his wife and child live, so of course, Wendy, so uptight she literally wears a girdle, is absolutely besotted with him. I mean, it just makes sense. Billy oozes a smug, “ain’t I a stinker?” self-assurance that makes one wonder how he doesn’t end up with his stupid saxophone wrapped around his neck.

As for Kirby, well, who gives a shit about him and his weird, stalkerish behavior. The movie sure doesn’t. Jules doesn’t get a lot to do either, except act as the catalyst to bring everyone together at the end, when, after losing her rich lover, her job, and all her belongings (except for a bitchin’ neon Billy Idol poster), she self-destructs and locks herself in her apartment, intending to let herself freeze to death. These great pals are so concerned for Jules that Kirby is cracking jokes, and Alec picks that exact time to get into a fight with Kevin over Leslie. Of course, it’s irresponsible manchild Billy who saves the day, breaking into Jules’ apartment and comforting her with a speech about how it’s normal to lose all your belongings to a crippling coke addiction, because “it’s our time on the edge.”

Don’t worry, everything’s fine at the end. Jules is fine. Kirby is fine. Kevin gets a front-page story in The Washington Post (titled, no shit, “The Meaning of Life”). He and Alec both agree to give Leslie time to decide which one of them she wants to be with, though obviously the answer is neither, especially not Kevin. Given what I’ve written here, you might think Billy is the worst character in St. Elmo’s Fire. No, it’s Kevin. At least Billy is upfront with who he is, a shitheel who would fuck a mailbox if it winked at him. Kevin is far more insidious, offering a sympathetic (and seemingly platonic) ear for Leslie’s problems while silently biding his time until he can make his move, when Leslie is at her most vulnerable. He’s a Nice Guy, before the phrase existed in that context, and the fact that anyone is still friends with him by the end of the movie, let alone Leslie, is nothing short of a miracle. If you take one thing away from this essay, let it be this:

As for Billy and Wendy, of course they end up sleeping together, because a legendary pussyhound is just the guy you want to make losing your virginity a memorable, meaningful experience. And then, just like that, Billy decides he’s going to leave to seek his fortune as an itinerant saxophone player/gas station attendant in New York City. His departure is hilariously solemn, as if he’s about to leave for Fort Dix instead of somewhere less than ninety minutes away by plane. There’s no mention at all of Billy leaving his child behind to follow his dreams—in fact, the lack of concern anyone expresses for how Billy’s behavior impacts his family is baffling, and does little to change the impression that these people might be the most self-absorbed twits ever to be immortalized on film. No, the real tragedy here is that he’s leaving Wendy, the woman he slept with exactly once and maybe kinda likes, but we’ll never know because none of these people ever fucking talk to each other until it’s too late.

Thus is the primary issue with St. Elmo’s Fire, other than it’s boring and that characters you’re presumably supposed to care about instead trigger an unreasonable white hot hatred. It’s an example of Roger Ebert’s “idiot plot,” in which much of the various conflicts that ensue could have been prevented with a conversation. Instead, Wendy suffers in mopey silence, while Kevin stews and exhibits grossly manipulative behavior. This is all portrayed as just stuff that happens when you leave college for the cold cruel adult world, and while it is, to be sure, it more often than not plays a distant second to real problems, like finding a job and trying to support yourself. You’ll note that, except for Billy, no one’s hurting for money in this movie. Alec and Leslie live in a loft big enough to double as a nightclub, while Wendy’s family tries to bribe her with promises of cash and a brand-new car if she dates a more suitable man than Billy. Of course the person they want to be with being with someone else is the worst thing that’s ever happened to them, what else do they have to worry about?

So yes, not that you really need reminding, but we fretted over frivolous things in our younger days too, it just wasn’t documented on Facebook or Instagram for all to see (and thank God for that). The only difference is that if a movie were to be made today focusing on a bunch of white, overprivileged dolts whose most pressing issue is who they’re supposedly in love with that week, it’d be treated as the eye-rolling nonsense it is, rather than serious, realistic drama. We lacked that one important quality that makes the difference: self-awareness.